2019 INTRODUCTION | PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | LINKS

Apollo launched Abbey’s rise at NASA

George Abbey’s storied NASA career truly began in Houston; poetic justice brought him to Rice, an institution present at the genesis of the space program.

George Abbey

In the ’60s, Abbey was a rising star among NASA’s dedicated engineers, earning the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Medal of Freedom, as a member of the operations team during the historic flight of Apollo 13. He eventually became the director of Johnson Space Center (JSC) before joining Rice’s James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy as the Baker Botts Senior Fellow in Space Policy in 2001.

As a young Air Force pilot and electrical engineer in the ’50s, Abbey was first assigned to the X-20 Dyna-Soar project, an Air Force program the Kennedy administration ultimately cancelled that would have sent a small space shuttle-type spacecraft in to orbit in the mid-’60s.

Assigned to Dyna-Soar at the Boeing plant in Seattle, Abbey was subsequently reassigned to NASA’s Apollo team. Ultimately as JSC director, he assumed responsibility for both the space shuttle and the international space station, NASA’s premier and most challenging programs. But when he first arrived in Houston, he was one of the hundreds of NASA engineers working to overcome the technical challenges of landing on — and returning from — the moon.

George Abbey, right, then technical assistant to the JSC director, at Mission Control during a test before the U.S.-U.S.S.R. Apollo-Soyuz mission to dock in Earth orbit. The photo was taken in March, 1975, four months before the successful mission.

Abbey spent the mid-’60s as part of the systems engineering team that developed the spacecraft’s command, service and lunar modules, but took a more administrative role after the Apollo 1 launch-pad fire in early 1967. Resigning his Air Force commission and joining NASA full time, Abbey became the technical assistant to George Low, the Apollo spacecraft program manager. He also was secretary of the Configuration Control Board set up by Low to resolve technical issues and implement the necessary changes for the program. He set the agenda for weekly meetings with key leaders of the NASA team and the contractor program managers. ”It was initially about the spacecraft changes needed subsequent to the Apollo 1 fire, but it became more than that,” he said. ”It became a forum to deal with all the technical issues on the program.

”I was George Low’s technical assistant, but more than that, he became my mentor. I was assigned to arguably NASA’s finest engineer and manager and certainly a great teacher. George got me involved in just about every aspect of the Apollo program, the design and development work, the testing and the operations end of it,” said the soft-spoken Abbey. ”After the Apollo 1 fire, everyone was conscious of the mandate Kennedy had given us about going to the moon and safely returning astronauts to Earth before the end of the decade. The pace of activities became even more intense, because we didn’t have that much more time.”

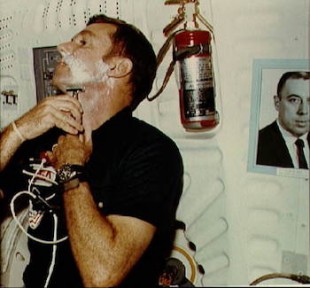

A photo of George Abbey adorns the space shuttle Columbia in 1981, watching over shaving astronaut Joe Engle.

Abbey was at Mission Control when the Apollo 11 lunar module touched down and recalled the ”uneasiness” in the room as computer alarms clanged and Armstrong looked for a landing site. ”There was a lot of anxiety up to the point when he finally made the call, and said, ‘Houston, the Eagle has landed.’

”People worked very hard to make sure it was going to work,” Abbey said. ”But until you see it actually there, and it happens, you’re never sure. There was a great sense of accomplishment and of elation. Of course, we also knew we had to get them back safely.”

Not many years later, Abbey would select the crews that flew during the early years of the space shuttle. As director of flight operations, he put America’s first woman in space when he assigned Sally Ride to the crew of 1983’s STS-7. Later, as director of JSC (1996-2001), Abbey was the man most responsible for the international space station, enlisting partner nations to share the adventure — and the costs — of a permanent outpost in Earth orbit.

Still, he doesn’t believe Apollo fulfilled its full potential. ”It should have continued,” he said. ”Apollo 11 was done to prove that we could do it. And then on Apollo 12, we were pretty much in the same mode, but we hadn’t gained any major science return from the missions. Science received a greater emphasis on Apollo 14 and with the addition of the lunar rover on Apollo 15, 16 and 17.”

But Abbey was glad to be there when Kennedy’s challenge was fulfilled. ”There was a great sense of pride and accomplishment throughout the agency.”

Leave a Reply