Rice University-based team analyzes physics of epithelial cell cooperation

Like flocks of birds, cells coordinate their motions as they race to cover and ultimately heal wounds to the skin. How that happens is a little less of a mystery today.

There’s a need to understand how cells cooperate to protect the site of a wound in the hours and days after injury, said Levine, who has introduced the first iteration of a computer model to analyze the two-dimensional physics of epithelial sheets. He hopes it will give new insight into a process with long-term implications not only for healing but also for understanding cancer, a prime motivator in his research since joining Rice under a grant from the Cancer Research and Prevention Institute of Texas.

A paper on the research by Levine, based at Rice University’s BioScience Research Collaborative, and colleagues at the University of California at San Diego and in Germany and France appears this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

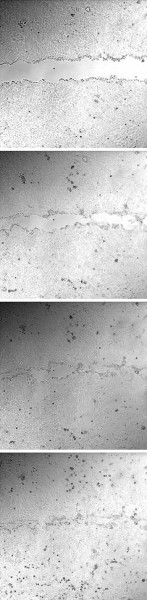

A sequence of images shows epithelial cells marching forward from the top and bottom to heal a wound. Images by Assaf Zaritsky/The Cell Image Library

Levine and his colleagues create computer models of processes seen by experimentalists to flesh out the rules that govern biological systems. “Here, we’re combining experimental observations from single cells with general notions from the physics literature to create an integrated way of thinking about this multicellular system,” he said.

The new models were prompted by a recent Harvard study showing “that even in the middle of a sheet, cells were dynamically creating heads and tails and were actively moving rather than being passively carried along,” Levine said. “This data convinced us that we needed a different way to start to think about the problem.”

The body marshals an astounding array of forces to heal wounds, Levine said. Many have to do with cell biology, the internal and external signals that tell a cell when to move, when to stop, when to split and when to die. His team’s intent was to focus first on the cell’s physical interactions with its neighbors and study what happened if all those complicating factors are eliminated from the simulations.

“We try to unravel what is physics and what is biology,” Levine said. “We want to know which parts of the phenomenon don’t require sophisticated signaling networks.”

In the physics approach to cell motility, he said, “the first thing to do is see how far we can get if we assume that all the cells are following the same rules. Then the only thing that’s creating the dynamics of the system is that they’re interacting with each other. This is the type of problem that physicists have studied before, usually in nonbiological contexts.”

In the Harvard experiment, he said, “They had taken a millimeter-sized tissue that was spreading and showed it wasn’t just cells on the end that were pulling on the tissue while the others were spectators.” But that work didn’t explain how cells in the center of the tissue knew the direction of the edge.

Levine’s team looked to the skies for inspiration. “Birds look around and decide which way all their neighbors are flying,” Levine said. “The idea that they would move as independent birds but also coordinate is where the idea of flocking came from. This way of thinking hadn’t been applied to epithelial tissue motility in wound healing.”

What cells “see” are their sticky neighbors, which pull and tug them as they move on lamellipodia, thin sheets that serve as “feet” powered by actin filaments that act something like the treads on a tank. The overlapping lamellipodia of adjacent cells influence each other. “The cells have to figure out which way to go based on competing tendencies: their own tendency to push on the ground and propel themselves forward, and the tendency of their neighbors to try to pull them in various directions,” Levine said. “Our basic notion is that as time goes on, these tendencies become correlated as the cell ‘tries’ to accommodate its conflicting inputs.”

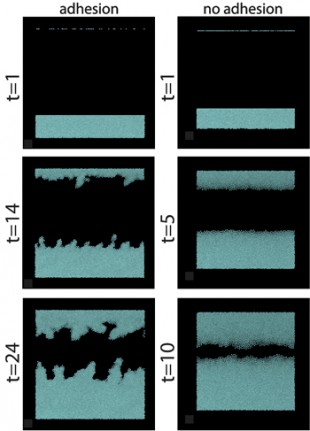

A simulation of epithelial cell growth shows how a wound heals from both sides when the individual cells move in a flock to repair the damage. Rice University researcher Herbert Levine said the cells that are “stickier” tend to push forward unevenly, with finger-like protrusions at the leading edge. In the left simulation, the cells were subject to the kind of adhesion they experience in real healing. At right, the adhesive properties of cells in the simulation were removed, resulting in much smoother -- though not necessarily more advantageous -- growth. Image by Markus Basan/University of California at San Diego

The Harvard experimentalists saw that loosely packed cells in the middle of a growing colony tend to swirl in a disorganized manner, and the simulations confirmed this. These swirls are analogous to what is seen in other examples of flocking. But when a wound is introduced, the swirls disappear and cells begin to match direction and velocity and pull toward a common goal. The ones on the edge immediately know which way to go, and everyone else learns from their example. Surprisingly, Levine said, “stickier” cells tend to push forward unevenly, with finger-like protrusions at the leading edge, much like what experimentalists often see.

The simulation model has a long way to go, Levine said. “It’s rough around the edges. Biologists who read this will immediately say, ‘You’ve left out all sorts of interesting things we know are happening.’

“Yes, there will be experiments for which this approach will not be sufficient,” he said. “It will teach us that in those cases, biology has to exert a more specific role in creating the structures and the motion.”

Levine hopes to match the models to current work by experimentalists on motility in cells related to the metastatic spread of breast cancer. “We’re a long way from saying anything about this problem,” he said. “But that’s my overall agenda — to push my research to where it can make contact with the cancer community.”

Co-authors of the new paper are postdoctoral researcher Markus Basan and senior scientist Wouter-Jan Rappel of the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics, University of California at San Diego; Jens Elgeti, a member of the scientific staff at the Institute of Complex Systems, Jülich, Germany; and Edouard Hannezo, a graduate student at the Curie Institute, Paris. Levine is the Karl F. Hasselmann Professor in Bioengineering at Rice and co-director of the Rice-based Center for Theoretical Biological Physics.

The National Science Foundation and its Center for Theoretical Biological Physics supported the research.

Leave a Reply