Editor’s note: Links to images for download appear at the end of this release.

David Ruth

713-348-6327

david@rice.edu

Mike Williams

713-348-6728

mikewilliams@rice.edu

Carbyne morphs when stretched

Rice University calculations show carbon-atom chain would go metal to semiconductor

HOUSTON – (July 21, 2014) – Applying just the right amount of tension to a chain of carbon atoms can turn it from a metallic conductor to an insulator, according to Rice University scientists.

Stretching the material known as carbyne — a hard-to-make, one-dimensional chain of carbon atoms — by just 3 percent can begin to change its properties in ways that engineers might find useful for mechanically activated nanoscale electronics and optics.

The finding by Rice theoretical physicist Boris Yakobson and his colleagues appears in the American Chemical Society journal Nano Letters.

Until recently, carbyne has existed mostly in theory, though experimentalists have made some headway in creating small samples of the finicky material. The carbon chain would theoretically be the strongest material ever, if only someone could make it reliably.

The first-principle calculations by Yakobson and his co-authors, Rice postdoctoral researcher Vasilii Artyukhov and graduate student Mingjie Liu, show that stretching carbon chains activates the transition from conductor to insulator by widening the material’s band gap. Band gaps, which free electrons must overcome to complete a circuit, give materials the semiconducting properties that make modern electronics possible.

In their previous work on carbyne, the researchers believed they saw hints of the transition, but they had to dig deeper to find that stretching would effectively turn the material into a switch.

Each carbon atom has four electrons available to form covalent bonds. In their relaxed state, the atoms in a carbyne chain would be more or less evenly spaced, with two bonds between them. But the atoms are never static, due to natural quantum uncertainty, which Yakobson said keeps them from slipping into a less-stable Peierls distortion.

“Peierls said one-dimensional metals are unstable and must become semiconductors or insulators,” Yakobson said. “But it’s not that simple, because there are two driving factors.”

One, the Peierls distortion, “wants to open the gap that makes it a semiconductor.” The other, called zero-point vibration (ZPV), “wants to maintain uniformity and the metal state.”

Yakobson explained that ZPV is a manifestation of quantum uncertainty, which says atoms are always in motion. “It’s more a blur than a vibration,” he said. “We can say carbyne represents the uncertainty principle in action, because when it’s relaxed, the bonds are constantly confused between 2-2 and 1-3, to the point where they average out and the chain remains metallic.”

But stretching the chain shifts the balance toward alternating long and short (1-3) bonds. That progressively opens a band gap beginning at about 3 percent tension, according to the computations. The Rice team created a phase diagram to illustrate the relationship of the band gap to strain and temperature.

How carbyne is attached to electrodes also matters, Artyukhov said. “Different bond connectivity patterns can affect the metallic/dielectric state balance and shift the transition point, potentially to where it may not be accessible anymore,” he said. “So one has to be extremely careful about making the contacts.”

“Carbyne’s structure is a conundrum,” he said. “Until this paper, everybody was convinced it was single-triple, with a long bond then a short bond, caused by Peierls instability.” He said the realization that quantum vibrations may quench Peierls, together with the team’s earlier finding that tension can increase the band gap and make carbyne more insulating, prompted the new study.

“Other researchers considered the role of ZPV in Peierls-active systems, even carbyne itself, before we did,” Artyukhov said. “However, in all previous studies only two possible answers were being considered: either ‘carbyne is semiconducting’ or ‘carbyne is metallic,’ and the conclusion, whichever one, was viewed as sort of a timeless mathematical truth, a static ‘ultimate verdict.’ What we realized here is that you can use tension to dynamically go from one regime to the other, which makes it useful on a completely different level.”

Yakobson noted the findings should encourage more research into the formation of stable carbyne chains and may apply equally to other one-dimensional chains subject to Peierls distortions, including conducting polymers and charge/spin density-wave materials.

The Robert Welch Foundation, the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Office of Naval Research Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative supported the research. The researchers utilized the Data Analysis and Visualization Cyberinfrastructure (DAVinCI) supercomputer supported by the NSF and administered by Rice’s Ken Kennedy Institute for Information Technology.

-30-

Read the abstract at http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/nl5017317

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews

Related Materials:

Yakobson Research Group: http://biygroup.blogs.rice.edu

Rice University Department of Materials Science and NanoEngineering: http://msne.rice.edu

Images for download:

https://news2.rice.edu/files/2014/07/0721_CARBYNE-1-WEB.jpg

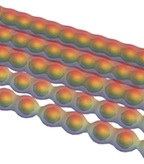

Carbyne turns from a metal to a semiconductor when stretched, according to calculations by Rice University scientists. Pulling on the ends would force the atoms to separate in pairs, opening a band gap. The chain of single carbon atoms would theoretically be the strongest material ever if it could be made reliably. (Credit: Vasilii Artyukhov/Rice University)

https://news2.rice.edu/files/2014/07/0721_CARBYNE-2-WEB.jpg

Carbyne chains of carbon atoms can be either metallic or semiconducting, according to first-principle calculations by scientists at Rice University. Stretching the chain dimerizes the atoms, opening a band gap between the pairs. (Credit: Vasilii Artyukhov/Rice University)

https://news2.rice.edu/files/2014/07/0721_CARBYNE-3-WEB.jpg

Rice University researchers, from left, Vasilii Artyukhov, Boris Yakobson and Mingjie Liu have calculated the effect of stretching on a carbyne chain of carbon atoms. The chain would go from a metal to a semiconductor. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,920 undergraduates and 2,567 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just over 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice has been ranked No. 1 for best quality of life multiple times by the Princeton Review and No. 2 for “best value” among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance. To read “What they’re saying about Rice,” go here.