Rice anthropologist examines how soldiers rebuild their lives after grievous war injuries

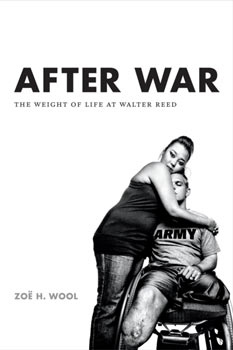

What’s life really like for soldiers at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Washington, D.C.? A new book by Rice anthropologist Zoë Wool takes an in-depth look at what life is like after the fighting ends.

In “After War,” Wool explores how America’s most severely injured soldiers struggle to return to ordinary life while recovering from extraordinary wounds at Walter Reed.

Wool is an assistant professor of anthropology who studies medical issues and is particularly interested in how disability and the body affect personhood. Between 2007 and 2008, she spent time with wounded soldiers, their families and loved ones in an effort to understand what it’s like to be seriously injured and transitioning back to civilian and family life. The soldiers, who were mostly male, each suffered life-altering injuries like lost limbs and traumatic brain injuries in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

“Having a family–in the very specific and normative sense of a married couple with children living in a single family household–emerges as the ultimate sign of successful rehabilitation and reincorporation into civilian life,” Wool said. “Family members live with injured soldiers at Walter Reed, so there are shades of that life there. But Walter Reed is both a place that holds out the promise of an ‘ordinary’ future and a place where the possibility of achieving it is brought into question.”

She said that one of the real challenges for soldiers is living up to the soldier stereotype most Americans believe – the idea all soldiers are pro-government “patriots” who support their government and military, no questions asked.

“In the U.S., there is no compulsory military service and, since 1973, no draft,” Wool said. “Soldiers inhabit a public imaginary that – especially in times of national anxiety – binds them to an exceptional form of personhood inflected with heroism and patriotic commitment.”

Wool said that over the course of her fieldwork, she realized that this traditional American profile of a soldier and what motivates him to serve his country is not always consistent with who soldiers actually are and their political views.

“Unfortunately, if a soldier doesn’t live up to this stereotype, it can affect how he is treated, both by veterans organizations and the public at large,” she said.

Wool noted that a number of veterans she worked with actually felt uncomfortable with the amount of attention they received for their “heroic” behavior.

“The guys I spent time with made it clear that being a soldier was their job — a job unlike others in many ways, but they thought of their injuries as having happened as part of their job, rather than being the outcome of patriotic sacrifice,” Wool said. “While glad to have recognition denied their Vietnam-era counterparts, they felt guilt when receiving special treatment or excessive attention couched in the language of gratitude and sacrifice.”

Wool ultimately hopes that the book will help shed light on the difficulties soldiers face in adapting to normal life after returning from war.

“One of the goals of the book is to get people to stop seeing injured soldiers and thinking things like ‘I could never imagine what you’ve been through.’ Of course, those who have never been to war can know what it’s like, but insisting that we can’t even try absolves us of the responsibility to think carefully about what war is and does in America, something I think we are obligated to do.”

For more information on “After War,” visit https://www.dukeupress.edu/after-war.

Leave a Reply