Five-year grant will support new simulations to advance ultracold physics

How cold can it get? Physicists don’t actually know, but Kaden Hazzard aims to find out.

Hazzard, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Rice, will pursue that question with backing from the National Science Foundation, which has named him the recipient of a prestigious CAREER Award, given to the nation’s most promising young faculty.

The five-year award for nearly $500,000 will allow Hazzard, a theoretical physicist, and his group to investigate new ways to simulate the states of matter at extreme cold temperatures, as close as possible to absolute zero. That could allow his experimental colleagues to bring into existence states of matter that are unavailable to them now.

“Materials in real life are bound by a set of rules, which are everything you study in materials science or solid-state physics,” he said. “But if we can find ways to break those rules, we can have materials with properties that nobody really imagined before.

“So our project is to figure out how to find types of matter that don’t yet exist,” he said.

Experimentalists create states like Bose-Einstein condensates, in which atoms reach their lowest quantum states and behave collectively, by making them extremely cold. A Rice colleague, Randy Hulet, was among the first to make a Bose-Einstein condensate when he cooled lithium gas to a millionth of a degree above absolute zero.

But that’s not cold enough to observe some exotic phases of matter they believe are possible.

“There have been spectacular advances, and I don’t want to minimize that, but there has been a sense of hitting a wall with current cooling methods,” Hazzard said. “Part of our research is to see if we can break through that frontier. Can we get another two or 10 or 100 times colder?”

The rules of quantum mechanics govern ultracold matter in ways not seen in the macro world, and simulations are useful tools to predict what happens there.

“To understand how to get colder, we also have to understand how really interesting quantum states move in time,” he said. “What are their dynamics?

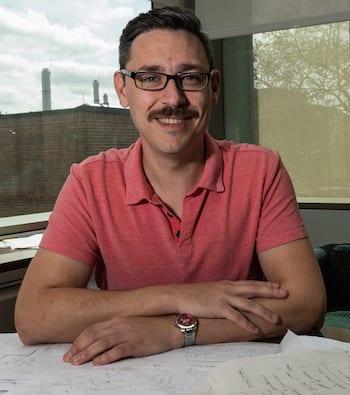

Rice theoretical physicist Kaden Hazzard with students Zhiyuan Wang, left, and Ian White, right. Hazzard and his group will use an NSF CAREER Award to investigate new ways to simulate the states of matter at extreme cold temperatures. Photo by Jeff Fitlow

“It’s a challenging problem,” he said. “You can’t solve this with pen and paper, and you can’t just put it on a computer. There are fundamental reasons it kills even the largest supercomputers to simulate the tiniest quantum systems. We need new ideas for how to simulate those systems on a computer.”

He said improved understanding of the relevant physics over the last 10 years will help his group build new simulations that point the way for experimentalists.

“We understand how correlations can grow in quantum systems,” Hazzard said. “We understand some constraints on how the quantum system can evolve, and by using those constraints, the hope is we can write very simple code that runs on a laptop and, for some type of problems, runs faster than the largest supercomputer with the previous best code.”

Hazzard’s grant will also allow him to create educational materials for high school through graduate students to train them to use what he called under-appreciated techniques in modern physics.

“There are concepts that practicing physicists use daily or routinely but they have not at all made their way into the physics curriculum,” he said.