Rice team’s intracranial pressure monitor will help docs diagnose infants at risk of brain damage

Feeling the soft spot atop a newborn’s head can give a doctor a sense of whether there’s too much pressure inside, but Rice University bioengineering students have found a way to get more comprehensive data without an invasive procedure.

The student team at Rice’s Brown School of Engineering created a seemingly simple but sophisticated system to monitor high intracranial pressure (ICP) within the skulls of infants, a condition that affects more than 400,000 every year. ICP can be caused by trauma to the brain and is a marker for hydrocephalus, a buildup of excess cerebral spinal fluid within the brain’s ventricles.

Their Bend-Aid, created in collaboration with Texas Children’s Hospital doctors at Rice’s Oshman Engineering Design Kitchen, combines an old-school adhesive bandage with a sensor that has the potential to replace two current techniques: Palpating the child’s soft spot to get a general sense of pressure, or drilling into the skull to insert an accurate but highly invasive sensor.

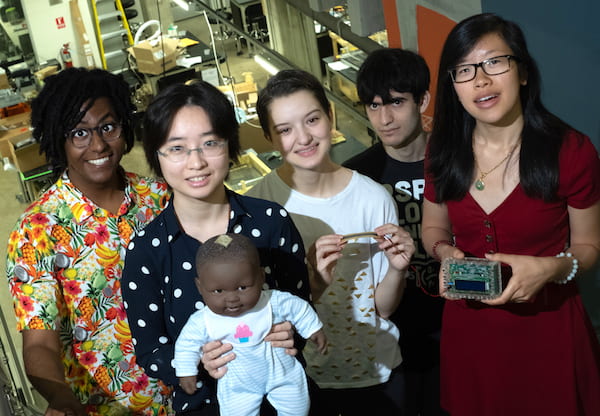

Rice senior Sammi Lu attaches a sensor to a mannequin to test a noninvasive system designed to monitor intracranial pressure in infants. Photo by Jeff Fitlow

The non-invasive method created by seniors Sammi Lu, Kiara Reyes Gamas, Tensae Assefa, Patricia Thai and Brett Stern allows clinicians to monitor babies for as long as necessary to build a record of intracranial pressure over time that would be impossible to acquire through occasional palpitation.

“What physicians usually do is feel the soft spot where the skull hasn’t fused together yet,” Thai said. “If it’s tense, that’s a sign of higher pressure. If it’s sunken, it’s low pressure. But it’s really subjective between doctors and previous research showed it’s not very accurate.

“There’s a need for a quantitative and continuous method to measure pressure in the skulls of infants, to see changes in ICP over time,” she said.

The team embedded a soft, ribbon-like sensor with a 2.2-inch working length into a bandage that, when affixed to the baby’s head, reports to a data processor when bent in or out by the changing shape of the soft spot, called the fontanelle. The fontanelle generally closes after 18 months as the skull plates fuse.

“From our literature search, we discovered there is a correlation of ICP levels within the skull space and the bending level of the fontanelle,” Lu said. The team used that data to build a mathematical model that correlates the sensor’s bending angle to standard measures of ICP.

A system developed by Rice engineering students is designed to monitor high intracranial pressure within the skulls of infants, a condition that affects more than 400,000 every year. Photo by Jeff Fitlow

The sensor feeds a processing unit that displays the numerical pressure level on an LCD screen. The system also stores data on an external SD card for later interpretation by other medical professionals.

“In actual cases, prolonged levels of ICP are more problematic than random spikes,” Lu said. “So we’ve built in an alarm system through the LED lights and a buzzer.”

The bandages are already in common use to dress wounds, Reyes Gamas said. “We tested it,” she said. “We put it on our arms and it stayed on for nine days. It will not come off unless you use ethanol on it. And we didn’t avoid any activities like exercising or showering; it’s pretty stable.

“We also tested the sensor itself to see if there was any change in accuracy over time in ideal conditions,” she said. “We found it was very consistent throughout.”

Dr. Sandi Lam, a pediatric neurosurgeon at Texas Children’s Hospital, and Dr. Vijay Ravindra, a pediatric neurosurgery fellow at Texas Children’s Hospital, worked with the team, who were advised by Sabia Abidi, a postdoctoral teaching fellow of bioengineering at Rice.