Rice’s laser-induced graphene nanogenerators could power future wearables

Wearable devices that harvest energy from movement are not a new idea, but a material created at Rice University may make them more practical.

The Rice lab of chemist James Tour has adapted laser-induced graphene (LIG) into small, metal-free devices that generate electricity. Like rubbing a balloon on hair, putting LIG composites in contact with other surfaces produces static electricity that can be used to power devices.

Lab video demonstrates that repeatedly hitting a folded triboelectric generator produced enough energy to power a series of attached light-emitting diodes. The test showed how generators based on laser-induced graphene could be used to power wearable sensors and electronics with human movement. Courtesy of the Tour Group

For that, thank the triboelectric effect, by which materials gather a charge through contact. When they are put together and then pulled apart, surface charges build up that can be channeled toward power generation.

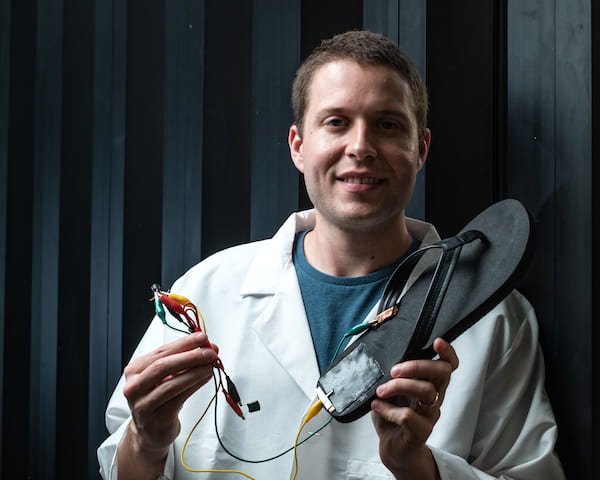

In experiments, the researchers connected a folded strip of LIG to a string of light-emitting diodes and found that tapping the strip produced enough energy to make them flash. A larger piece of LIG embedded within a flip-flop let a wearer generate energy with every step, as the graphene composite’s repeated contact with skin produced a current to charge a small capacitor.

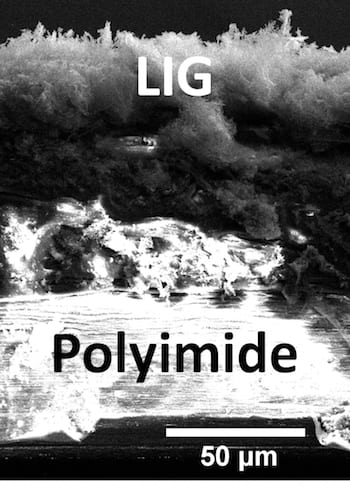

An electron microscope image shows a cross-section of a laser-induced graphene and polyimide composite created at Rice University for use as a triboelectric nanogenerator. The devices are able to turn movement into energy that can then be stored for later use. Courtesy of the Tour Group

“This could be a way to recharge small devices just by using the excess energy of heel strikes during walking, or swinging arm movements against the torso,” Tour said.

The project is detailed in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Nano.

LIG is a graphene foam produced when chemicals are heated on the surface of a polymer or other material with a laser, leaving only interconnected flakes of two-dimensional carbon. The lab first made LIG on common polyimide, but extended the technique to plants, food, treated paper and wood.

The lab turned polyimide, cork and other materials into LIG electrodes to see how well they produced energy and stood up to wear and tear. They got the best results from materials on the opposite ends of the triboelectric series, which quantifies their ability to generate static charge by contact electrification.

In the folding configuration, LIG from the tribo-negative polyimide was sprayed with a protecting coating of polyurethane, which also served as a tribo-positive material. When the electrodes were brought together, electrons transferred to the polyimide from the polyurethane. Subsequent contact and separation drove charges that could be stored through an external circuit to rebalance the built-up static charge. The folding LIG generated about 1 kilovolt, and remained stable after 5,000 bending cycles.

The best configuration, with electrodes of the polyimide-LIG composite and aluminum, produced voltages above 3.5 kilovolts with a peak power of more than 8 milliwatts.

Rice University postdoctoral researcher Michael Stanford holds a flip-flop with a triboelectric nanogenerator, based on laser-induced graphene, attached to the heel. Walking with the flip-flop generates electricity with repeated contact between the generator and the wearer’s skin. Stanford wired the device to store energy on a capacitor. Photo by Jeff Fitlow

“The nanogenerator embedded within a flip-flop was able to store 0.22 millijoules of electrical energy on a capacitor after a 1-kilometer walk,” said Rice postdoctoral researcher Michael Stanford, lead author of the paper. “This rate of energy storage is enough to power wearable sensors and electronics with human movement.”

Co-authors of the paper are Rice graduate students Yieu Chyan and Zhe Wang and undergraduate students John Li and Winston Wang. Tour is the T.T. and W.F. Chao Chair in Chemistry as well as a professor of computer science and of materials science and nanoengineering at Rice.

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research supported the research.