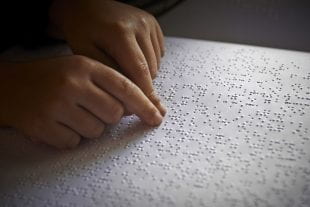

First-of-its-kind research will examine how instructors understand and teach writing system for blind students

Braille provides a pathway to literacy for the visually impaired. But research shows that blind students typically demonstrate lower literacy rates than their peers without visual impairment.

A first-of-its-kind study at Rice University will seek to improve braille literacy by exploring questions about how it’s taught. Some teachers see braille as a code representing print, while others consider it a writing system serving as a direct path to literacy. The research will examine how an instructor’s view of the system affects students.

The research funded by a $1.4 million grant from the Institute of Education Sciences will be conducted by Robert Englebretson, an associate professor and chair of linguistics at Rice; Simon Fischer-Baum, an assistant professor of psychological sciences at Rice; and Cay Holbrook, a professor of special education at the University of British Columbia. The interdisciplinary study will draw on the researchers’ respective areas of expertise: language structure, neuroscience and reading, and blindness and braille pedagogy.

Tactile reading has been mostly unexplored in the cognitive sciences, Englebretson said, despite being a critically important topic for the visually impaired.

“Early and effective braille instruction is critical to promote proficiency in school and after,” he said. “TVIs (teachers of students with visual impairments) are typically the primary link to braille literacy for learners who are blind. Yet there has been limited research on factors that underlie TVIs’ teaching of braille, including their experience and beliefs, attitudes and assumptions about braille, and their understanding of how tactile reading works.”

Fischer-Baum said he and his fellow researchers believe there is a disconnect between how blind students and most TVIs read braille.

“Most TVIs are sighted and have a lifetime of experience with print by the time they learn braille, so they typically read by sight rather than by touch,” he said. “In contrast, for students who are blind, braille is often the first and primary way that they read. “We want to understand how this disconnect in experience affects the way TVIs teach braille to their students.”

Some instructors believe that braille is a code representing print rather than a pathway to literacy. That’s one point the researchers will consider as they survey TVIs to gauge their experience, attitudes and beliefs regarding braille, as well as their confidence in teaching it.

“There are important differences between print and braille – it’s not a 1-to-1 correspondence,” Fischer-Baum said. “This can result in some confusion. For example, imagine you’re teaching a child to read the word ‘seed.’ You’re teaching them to look for the ‘ee’ and sound out this long ‘e’ sound. However, ‘ed’ in braille is a contraction and an example of a single symbol that corresponds to more than one letter in print.”

“Braille teachers who think about braille as a transcription system for print will say the same thing to their sighted students as students learning to read braille,” he said. “But, there is no ‘ee’ in this word when you read braille — there’s ‘s’ and an ‘e’ and an ‘ed’ symbol — and so for a student to be able to see that ‘ee’ that corresponds to a sound, they have to unpack that ‘ed,’ and this decoding and recoding is simply not how children generally learn to read.”

Englebretson, a braille reader himself, said this idea of braille as a code that readers have to decode before accessing a word’s meaning slows down learners and impacts literacy.

The study will also collect data from visually impaired students to try to determine how their understanding of braille relates to their own proficiency. They will specifically look at the relationship between students and their teachers to see how their assumptions and skills match up. In addition, they will measure braille reading comprehension among students and measure how TVIs and adult braille readers process braille to determine if there are any differences.

“A more accurate understanding of braille reading will lead to better teaching materials that leverage the perceptual and cognitive processes that braille readers actually use, rather than assuming the decoding processes that print readers bring to the task,” Englebretson said.

The researchers feel strongly that gaining a better understanding of how people read braille will help to fix the disconnect between teaching and learning compared to students without visual impairment.

The study will include approximately 200 credentialed TVIs who have taught at least one braille-reading student during the previous two years as well as 50 adults who are proficient braille readers. The researchers will also analyze writing samples and other data from approximately 1,800 blind students in grades 1-12 from the U.S. and Canada.

The researchers plan to circulate the study’s results through various publications and presentations. They also hope to organize a symposium to influence education stakeholders, including practitioners and policymakers.

“Braille literacy is crucial for the success of individuals who are blind — at school, at work and in leisure,” Englebretson said. “The low rates of braille literacy are disadvantaging an already disadvantaged segment of society, and it is genuinely exciting to work on a project that will bring about a more level playing field.”

For more information on the grant, visit https://ies.ed.gov/funding/grantsearch/details.asp?ID=3297.