Water is easy to take for granted, but a new book from a Rice University anthropologist examines what it takes to make water accessible.

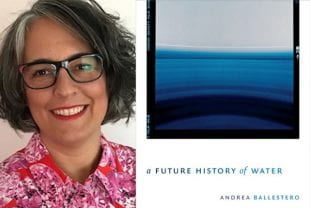

“A Future History of Water” (Duke University Press, 248 pages, $24.95) traces what Andrea Ballestero, an associate professor of anthropology at Rice and environmental ethnographer, calls the “unspectacular work” to make water access “a human right and not a commodity.”

“It is definitely something many take for granted and assume is happening,” she said of clean water access in the U.S. “But as we’ve seen recently in Flint, Michigan, it is not always guaranteed. It is a mistake to assume it is.”

In places such as Ballestero’s native Costa Rica, where most people have access to clean water, questions remain about its affordability.

The book, her first, is based on field research among state officials, nongovernmental organizations, politicians and activists in Costa Rica and Brazil. It shows the reader the often-invisible technicalities behind water access.

Ballestero worked alongside not only people involved in social movements fighting for water as a human right, but also with regulators using tools such as pricing formulas and the consumer price index to consider society’s responsibility regarding access.

“I was interested in knowing what water as a human right really means,” she said. “Does it mean that it is clean? That it is priced at a certain level? These are many of the questions that people answer practically every day, all around the world.”

Over the course of her research, Ballestero became particularly focused on mid-level bureaucrats in Costa Rica and Brazil, individuals she said have a “huge” responsibility for important moral and ethical decisions surrounding water rights and access. She was especially interested in how they were translating the idea that water is a human right and not a commodity.

“These individuals are very aware of the responsibility and power they have,” she said.

Ballestero hopes her book will inspire people to recognize that how we manage, distribute and access water reflects who we are as a community. She shows that while infrastructure is critical, pricing formulas, legal categories and political promises are just as important, highlighting the need to focus on seemingly minor technical choices that in reality embody fundamental questions of social and environmental justice.

For more information on the book, visit https://www.dukeupress.edu/a-future-history-of-water. To download a free electronic copy, visit http://oapen.org/search?identifier=1005198.