Graduate student Azizou Atte-oudeyi found his way to Rice University in perhaps the Rice-iest way possible: by typing “unconventional university” into a search engine. But as he likes to say, there’s more to the story than that.

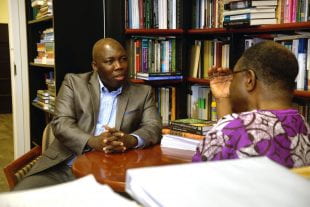

An unexpected conversion experience led Azizou Atte-oudeyi from a career in diplomacy to academia, pursuing his Ph.D. in religion at Rice. (Photo by Jeff Fitlow)

At the beginning of 2016, Atte-oudeyi was working as a diplomat for the State Department. After two years as a Pickering Graduate Fellow, he was stationed in Ivory Coast as a vice consul. It was close to his home country of Togo, allowing him to visit his family and travel throughout Africa. For a moment, at least, it was everything Atte-oudeyi wanted.

Overnight, it all changed.

“I was born Muslim and grew up Muslim,” Atte-oudeyi said. “In 2016, I had this strange conversion to Christianity. I started asking myself a lot of questions — and I couldn’t find the answers.”

This unexpected conversion experience led Atte-oudeyi to dive deep into theological deliberations and scholarly works on the internet. But for an intellectual who values the engagement that comes from learning in a collegiate fashion — “I always want to understand things,” he said — the online research simply wasn’t enough. Atte-oudeyi knew the only step that could satisfy him was a thorough education on religion.

“When I went to the Rice website and I read it, I said, ‘This is the right place; this is where I need to go to ask my questions,” Atte-oudeyi said. “And so I resigned my job and I came here. ‘Unconventional wisdom’ is what brought me here.”

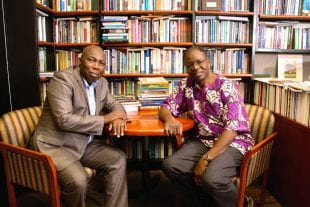

As a doctoral candidate in the Department of Religion, Atte-oudeyi works closely with department chair Elias Bongmba, the Harry and Hazel Chavanne Professor of Christian Theology. (Photo by Jeff Fitlow)

That was one year ago. Since then, as a doctoral candidate in the Department of Religion, Atte-oudeyi has found a few answers reading Hume and Hegel, studying African religions and Arabic texts, and discussing everything from Paul and the New Testament to the intertwining history of Islam and Christianity in Africa.

Atte-oudeyi was the only Rice representative in this year’s National Humanities Center Graduate Student Summer Residency program, which focused on using interactive geospatial technologies to create inquiry-based maps. There, he further developed the mapping skills he became familiar with while working as a U.S. Refugee Coordinator in Ivory Coast. He’s since spent hours in the GIS/Data Center inside Fondren Library, considering methods for mapping themes in religion such as the Seven Churches of Revelation or the global spread of Pentecostalism.

He’s also discovered even more questions along the way — but that’s the point, he said.

“What I have come to understand is that we’re always vested in our careers, our jobs,” Atte-oudeyi said. “We run after that. We want to be seen. We want to make it, have a nice house, a beautiful car. But we never stop to ask who I am or why I’m here. We want to be a diplomat, an architect, a scientist, but we never ask the real questions. And that’s what humanities does. Humanities asks the big questions.”

Born into a family of 10 in Togo, Atte-oudeyi visited the American embassy library in the capital city of Lomé for the first time at the age of 13. It was an experience almost as transformative as his conversion: Atte-oudeyi would soon travel to America on a diversity visa and become a U.S. citizen in 2005. He was sworn in as a U.S. foreign service officer in 2013, and the experiences he had across Africa in that role opened his eyes to two significant things.

“Through my travels I saw a lot of religiosity in Africa,” he said. “They’re so much into God. What’s the relation? Why is this happening?”

At the same time, Atte-oudeyi said, this abundance of religion thrived alongside an abundance of suffering. Was there a relationship there, too? What is religion’s role in alleviating or perpetuating suffering? And how can studying this intersection help others?

With four years left to complete his Ph.D., Atte-oudeyi still has plenty of time to search for the answers to those questions — and to determine what his work as a diplomat-turned-scholar will ultimately contribute to the world at large.

“I don’t know where this is going to lead me, but I know it’s going to lead me somewhere,” Atte-oudeyi said. “It’s going to lead me to touch other people’s lives, to change lives, and that would make me really, really happy. To transform other people’s lives, that’s my goal.”