NEWS RELEASE

Jeff Falk

713-348-6775

jfalk@rice.edu

Mike Williams

713-348-6728

mikewilliams@rice.edu

Tissue-digging nanodrills do just enough damage

Scientists advance case for use of molecular machines to treat skin diseases

HOUSTON – (March 5, 2020) – Molecule-sized drills do the damage they are designed to do. That’s bad news for disease.

Scientists at Rice University, Biola University and the Texas A&M Health Science Center have further validation that their molecular motors, light-activated rotors that spin up to 3 million times per second, can target diseased cells and kill them in minutes.

The team led by Biola molecular biochemist Richard Gunasekera and Rice chemist James Tour showed their motors are highly effective at destroying cells in three multicellular test organisms: worms, plankton and mice.

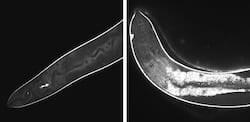

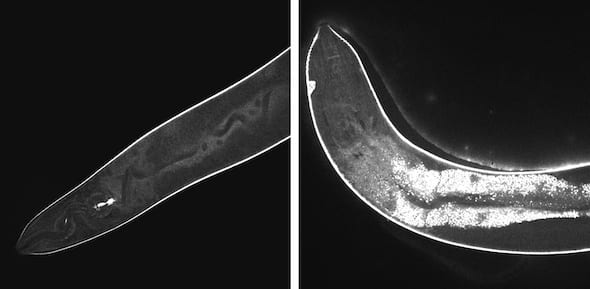

High-resolution confocal images show the effects of light-activated molecular drills on cells inside a worm. Before activation, at left, the injected drills remain dark. At right, after 15 minutes of exposure to light, fluorescent signals show widespread damage in the transparent nematodes. The drills developed at Rice University are intended to target drug-resistant bacteria, cancer and other disease-causing cells and destroy them without damaging adjacent healthy cells. Image by Thushara Galbadage/Biola University

A study in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces shows the motors caused various degrees of damage to tissues in all three species. The journal plans to designate the paper as an open-access ACS Editors’ Choice.

The project’s original goal was to target drug-resistant bacteria, cancer and other disease-causing cells and destroy them without damaging adjacent healthy cells. Tour has argued cells and bacteria have no possible defense against a nanomechanical drilling force strong enough to punch through their walls.

“Now it has been taken to a whole new level,” Tour said. “The work here shows that whole organisms, such as small worms and water fleas, can be killed by nanomachines that drill into them. This is not just single-cell death, but whole organism, with cell death in the millions.

“They can also be used to drill into skin, thereby suggesting utility in the treatment of things like pre-melanoma,” he said.

The researchers saw different effects in each of the three models. In the worm, C. elegans, the fast motors caused rapid depigmentation as the motors first caused nanomechanical disruption of cells and tissues. In the plankton, Daphnia, the motors first dismembered exterior limbs. In both cases, after a few days, most or all of the organisms died.

For mouse models, researchers applied the nanomachines in a topical solution to the skin. Activating the fast motors caused lesions and ulcerations, demonstrating their ability to function in larger animals.

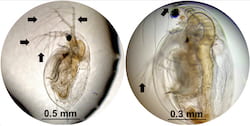

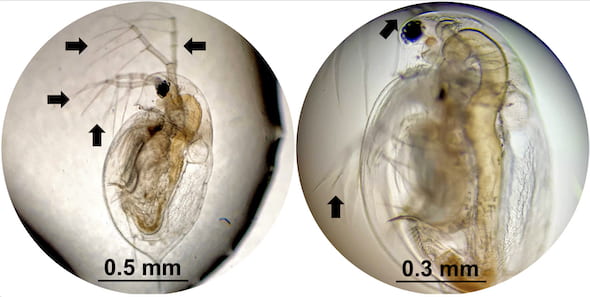

Daphnia, a species of plankton, were exposed to molecular machines developed at Rice University in lab experiments to determine the effects of the microscopic drills on tissue. At left is a healthy plankton with all of its appendages. At right, the daphnia has only two of its appendages after 10 minutes of exposure to light-activated nanomachines. The drills are intended to target drug-resistant bacteria, cancer and other disease-causing cells and destroy them without damaging adjacent healthy cells. Images by Alison Buck/Biola University

“That mouse skin changes due to the ‘drilling’ by the nanomachines might be the one of most interesting aspects of the study to scientists,” said Gunasekera, an adjunct faculty member and former visiting scientist at Rice and currently associate dean and a professor of biochemistry at Biola. He is co-lead author of the paper with Thushara Galbadage, an associate professor of public health at Biola.

“It could mean direct topical treatment to skin conditions such as melanomas, eczema and other skin diseases,” Gunasekera said. “This paper is significant because it’s the first testing of nanomachines where we’ve proven its effectiveness in vivo. All other studies done so far were done in vitro.”

He suggested the motors could be used for therapeutic parasite control as well as local treatment of such diseases as skin cancer.

Co-authors of the paper are Ciceron Ayala-Orozco, an academic visitor at Rice and postdoctoral fellow at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center; Rice postdoctoral researchers Dongdong Liu and Victor García-López; Rice alumnus Brian Troutman, a senior project engineer at Lockheed Martin; Rice academic visitor Josiah Tour; Robert Pal, a Royal Society University Research Fellow at Durham (U.K.) University; Sunil Krishnan, a professor of radiation oncology at MD Anderson, and Jeffrey Cirillo, a Regents’ Professor and director of Texas A&M’s Center for Airborne Pathogen Research and Tuberculosis Imaging. Tour is the T.T. and W.F. Chao Chair in Chemistry as well as a professor of computer science and of materials science and nanoengineering at Rice.

The Discovery Institute, the Welch Foundation and the National Institutes of Health supported the research.

-30-

Read the abstract at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.9b22595.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews.

Related materials:

Motorized molecules drill through cells: http://news.rice.edu/2017/08/30/motorized-molecules-drill-through-cells-2/

Tour Group: http://www.jmtour.com

Richard Gunasekera: https://www.biola.edu/directory/people/richard-gunasekera

Department of Chemistry: https://chemistry.rice.edu

Wiess School of Natural Sciences: http://natsci.rice.edu

Images for download:

https://news2.rice.edu/files/2020/03/0309_MACHINES-1-WEB.jpg

High-resolution confocal images show the effects of light-activated molecular drills on cells inside a worm. Before activation, at left, the injected drills remain dark. At right, after 15 minutes of exposure to light, fluorescent signals show widespread damage in the transparent nematodes. The drills developed at Rice University are intended to target drug-resistant bacteria, cancer and other disease-causing cells and destroy them without damaging adjacent healthy cells. (Credit: Thushara Galbadage/Biola University)

https://news2.rice.edu/files/2020/03/0309_MACHINES-2-WEB.jpg

High-resolution confocal images show the effects of light-activated molecular drills on cells inside a worm. Before activation, at top, the injected drills remain dark. At bottom, after 15 minutes of exposure to light, fluorescent signals show widespread damage in the transparent nematodes. The drills developed at Rice University are intended to target drug-resistant bacteria, cancer and other disease-causing cells and destroy them without damaging adjacent healthy cells. (Credit: Thushara Galbadage/Biola University)

https://news2.rice.edu/files/2020/03/0309_MACHINES-3-WEB.jpg

Daphnia, a species of plankton, were exposed to molecular machines developed at Rice University in lab experiments to determine the effects of the microscopic drills on tissue. At left is a healthy plankton with all of its appendages. At right, the daphnia has only two of its appendages after 10 minutes of exposure to light-activated nanomachines. The drills are intended to target drug-resistant bacteria, cancer and other disease-causing cells and destroy them without damaging adjacent healthy cells. (Credit: Alison Buck/Biola University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,962 undergraduates and 3,027 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 4 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.