How a medical humanities workshop and coding crash course created a pulse-inspired art exhibition at Rice’s Solar Studios

When was the last time you felt your own pulse? Touched that delicate flow of fluids on your own wrist? Or felt for the carotid thumping under your jaw?

As one of the body’s four main vital signs, the pulse was the only window physicians had into the workings of the human heart for thousands of years. The earliest Chinese, Greek, Egyptian and Arab medical practitioners knew its significance; many of them specialized in pulse-taking as a diagnostic tool for determining much more about a patient’s health than just their heart rate. Within most modern medical settings, however, the human pulse is usually taken by a machine rather than another human.

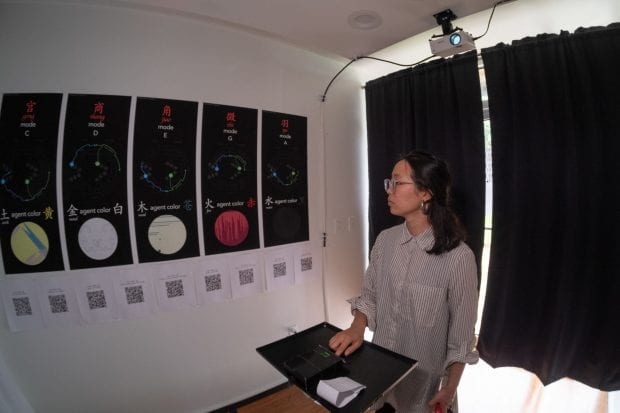

PULSES | PROCESSING, an exhibition currently on display at Rice’s Solar Studios, inspires visitors to ponder such often unconsidered aspects of pulse, or palpation, including the relatively new sort of physical distancing that removes human touch from the equation — and therefore from the diagnosis.

The result of a four-day workshop hosted last July by Rice assistant professor of history Lan Li and Columbia University collaborator Tristan Revells, PULSES | PROCESSING is a collaborative art installation created via a crash course in coding and medical humanities. The exhibit spans the Solar Studios’ three gallery spaces at the corner of College Way and Alumni Drive and runs through June 21.

“There are many scholars of pulses, because pulses have been foundational to understanding how medical practices have shared similarities and diverged over time around the world,” said Li, a historian and filmmaker who focuses on medicine and health in global East Asia.

The exhibition in Rice’s Solar Studios runs through June 21 and is open to the public from 10 to 6 Monday to Friday and noon to 4 Saturday and Sunday.

Li’s workshop aimed to teach humanities scholars creative coding while also rendering early modern Chinese and European styles of pulse-taking — a qualitative, affective mode of haptic inquiry — into biometric art. The aesthetic transformation of pulse into sound, image and animation not only transforms the body into art, Li said, but also introduces otherwise ignored cosmologies of the body into the everyday.

Using a rich array of primary sources, Li and the workshop’s guest speakers — representing classics, design, music, art history and science studies — illuminated the history of the vital sign and the many ways in which the pulse has been recorded and observed across time and cultures.

The first-of-its-kind workshop, which was sponsored by the Humanities Research Center’s Spatial Humanities Initiative, also taught students how to use a visually oriented, open-source coding language called Processing, which is based on Java.

Revells — a member of the creative coding community and chief operating officer of OFCourse, a Shanghai-based design and tech platform — taught students to use Processing for such purposes as translating haptic sensations, such as the beat of a human pulse, into animated shapes, sounds and colors.

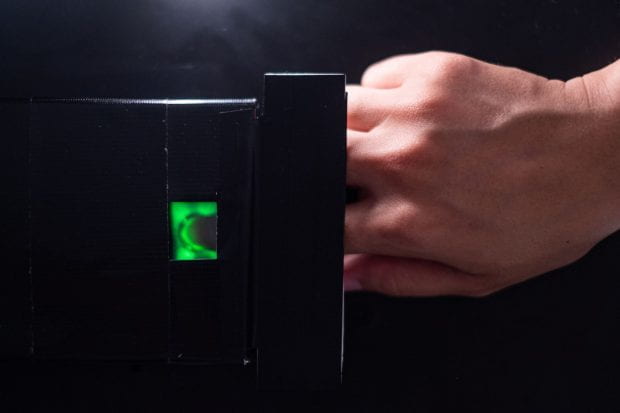

Visitors use an Arduino-equipped sensor and their own heartbeat to generate unique visuals and tones within the exhibition.

Processing is also commonly used among artists and can be connected to microprocessor boards like an Arduino. In one of the Solar Studio installations for PULSES | PROCESSING, visitors are invited to place their own finger on just such an Arduino-equipped sensor and use their own heartbeat to generate unique visuals and tones within the exhibition.

In addition to providing students a new level of coding literacy, Li invited guest speakers to the workshop: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston curator James Clifton and Texas A&M University art history professor Tianna Uchacz joined the group to discuss visual art, for instance, while John Mulligan in Rice’s Center for Research Computing discussed visual data.

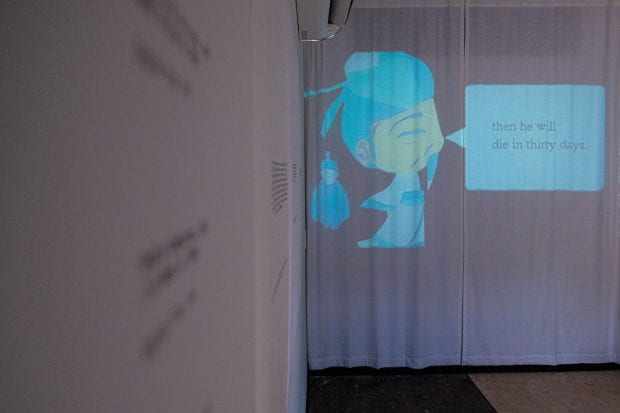

Students also learned to build an interactive audio player for the exhibition in addition to creating and editing videos. They then worked as a group to install their visualizations of various biomedical pulse data in thought-provoking displays across the Solar Studios.

The workshop itself was completed via Zoom last year, making this May’s installation the first time the group all met in person. Clifton brought his years of curatorial experience to bear in guiding the process. The end result is striking in its creativity and breadth of collaboration.

Students learned to build an interactive audio player for the exhibition in addition to creating and editing videos.

“The students were really proud,” said Li, who noted that one junior even walked his parents through the entire exhibit over FaceTime. “I had never built and maintained an exhibition, so it was a learning curve for all of us.”

Li also remarked on the way students learned more about themselves in the process, including a newfound sensitivity to the feel of people’s pulses, as well as the unusually collaborative nature of the workshop and exhibition.

“It’s highly experimental because it’s deeply interdisciplinary. We really worked to engage across different scholarly fields and institutions,” said Li, whose own courses in medical humanities span fields such as religion, science and technology. “We’re playing with the boundaries of what ‘biometrics’ means by using art, textures, music and colors to capture the full cosmology of embodied practices.”

PULSES | PROCESSING runs through June 21 in Rice University’s Solar Studios, which are free and open to the public during operating hours. For more information, visit pulses.blogs.rice.edu.