Precious few Jewish people lived in early Colonial America. Historians surmise that Jews in North America during that time accounted for less than a tenth of a percent of the entire population. Yet by Rice professor Brian Ogren’s estimation, Jewish ideas and beliefs — including the esoteric strand of Judaism known as kabbalah — significantly influenced Puritan and other Protestant non-Jewish thinkers of the era.

This profound impact was something Ogren, the Anna Smith Fine Assistant Professor of Judaic Studies, stumbled upon while doing research within his broader field of study, Jewish thought in the early modern period in Europe. In particular, he researches the history of Jewish philosophy and kabbalah as modes of thought that seek a more personal relationship with and understanding of God through the reading and interpretation of sacred texts.

Ogren has found a strong connection, in this regard, between Jewish interpretation and various aspects of Colonial American thought.

Cotton Mather, infamous for his role in the Salem witch trials, was a well-known Puritan minister and one of the most influential North American theologians of his time. Mather’s biblical commentary written between 1693 and 1728, “Biblia Americana,” has been compared to “an eclectic Jewish midrash.” It employed Jewish thought “in a very sophisticated manner,” Ogren said, including a vast array of Jewish philosophical and mystical sources.

Then there was the seventh president of Yale University. Ezra Stiles, who served in that role from 1788 to 1795, “became fascinated by Jewish thought, in particular Jewish mysticism” over time, Ogren said. Stiles — who was Yale’s first professor of Semitics — incorporated this interest into scholarly life at the university, requiring Hebrew classes and referencing it often in speeches. (His first commencement address was ostensibly delivered in Hebrew.) Stiles also maintained close relationships with various rabbis from Europe and the Near East, as the U.S. wouldn’t even have its first ordained rabbi until 1840.

Once Ogren noticed these connections between early modern Jewish ideas and the nascent philosophies of new Americans, there was no looking back.

“You start peeling back the layers and finding all kinds of things,” he said.

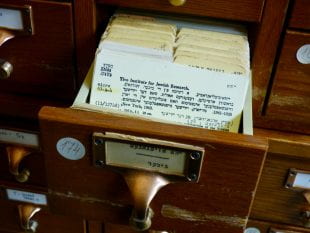

Ogren will soon begin a year of research at the Center for Jewish History in New York as a National Endowment for the Humanities Senior Scholar.

Soon, Ogren will have even more layers to peel back: He begins a year of research at the Center for Jewish History in New York this summer. While there, Ogren will be a National Endowment for the Humanities Senior Scholar, in which role he will lead a cohort of graduate research fellows while simultaneously working on his own book.

Thanks to this competitive and prestigious grant, as well as generous research support from Rice’s very own Jewish Studies Program, Ogren will spend the next 12 months in the archives of the largest repository of Jewish history in the United States. He’s already got his eye on a few items within the stacks.

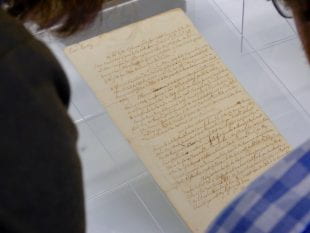

“They have an original copy of the very first rabbinic sermon given in the New World, in Rhode Island, by a rabbi visiting from Hebron,” Ogren said.

Dating to May 28, 1773, the sermon was delivered in Spanish — a reflection of the active Sephardic tradition of the time. The CJH’s archived copy is one of the rare existing printed versions, which was transcribed and published in English; according to Ogren, this fact itself may very well be reflective of its intended reach to English-speaking Protestants.

Then there’s an original copy of Judah Monis’s Hebrew grammar lessons, written out by hand by one of his students at Harvard University, where Monis taught between 1722 and 1760. The first full-time Hebrew instructor in North America, Monis was also the first Jew to receive a degree in the American Colonies.

“I’m very excited about this whole experience for the sole reason of being able to plumb the archives,” Ogren said.

Ostensibly the descendent of conversos himself, Monis converted to Congregational Christianity prior to teaching at Harvard. It was a controversial move in many circles, with his contemporaries referring to Monis alternately as “the converted rabbi” or “the Christianized Jew.”

“Here we have a figure with a complex, mingled identity. He’s Jewish in background, and in the eyes of his Protestant students and colleagues, but no longer really Jewish in the eyes of the Jewish community,” Ogren said of the scholar, who was born and educated in Italy and, later, Amsterdam. “He’s gone through all kinds of Jewish learning on the European continent and comes to the New World and brings this with him.”

As a part of this ongoing project, Ogren will be visiting Amsterdam this summer before arriving in New York. In the Netherlands, he’ll give a talk at an international conference and explore the archives of Monis’s old stomping-grounds.

At the same time figures like Monis were bringing information and ideas from Jewish mystical circles in Europe to the New World, Puritan leaders like Increase Mather — Cotton Mather’s father and president of Harvard for 20 years — were using incidents of Jewish conversion to push their own agendas: converting all the Jews to Christianity, for instance. Others employed kabbalistic ideas to argue that the culmination of Jewish mystical thought was actually Jesus Christ in the form of a bridge between God and man.

Handwritten materials from the Colonial period in America are among the treasures within the CJH archives.

As these new Americans became more and more aware of Jewish thought, Ogren said, they began utilizing it to show what was, in their minds at least, “the ultimate truth in Christianity.” At the same time, he said, “they were trying to forge a whole new identity, in some way, with these ideas and principles.”

Or, as Edward O’Reilly recently wrote for the New-York Historical Society, “New England Puritans styled themselves as New World Israelites, envisioning parallels between their own story carving a Christian civilization out of the wilderness and the experience of Old Testament Jews.”

Ogren hopes to find even more examples of this emerging school of thought, especially as influenced by Jewish philosophy and kabbalah, during his year at the CJH.

“If nothing else, I’m very excited about this whole experience for the sole reason of being able to plumb the archives,” he said. “And who knows what I’ll find there?”

Ogren’s last yearlong research trip — to Villa I Tatti, Harvard’s Center for Italian Renaissance Studies in Florence, Italy — netted enough material for a book. With any luck, he’ll be able to find enough material in the CJH archives during this trip for another monograph.

“That’s the goal,” he said. “At least to be far enough along that I should be able to turn this whole project into a book.”