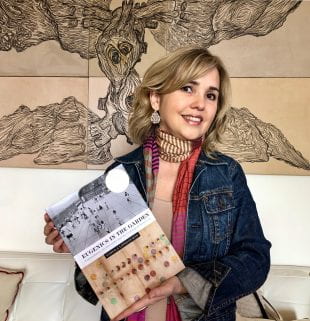

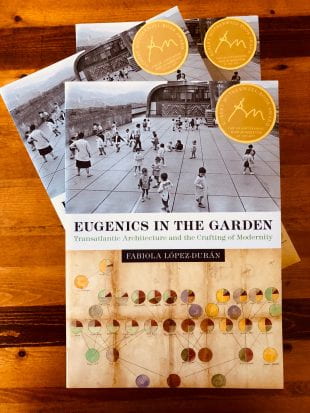

With her 2018 book “Eugenics in the Garden: Transatlanctic Architecture and the Crafting of Modernity,” Fabiola López-Durán was the first scholar to link eugenics — the movement that sought the improvement or “whitening” of the human race — with architecture.

Fabiola López-Durán won the 2019 Motherwell Award for her book linking eugenics with architecture and urban planning.

This month, the Rice associate professor of art history’s book won the 2019 Robert Motherwell Book Award. This annual prize from the Dedalus Foundation, along with a check for $10,000, is awarded to the author of an outstanding publication on the history and criticism of modernism in the arts. López-Durán shared this honor with Carol Armstrong, professor of art history at Yale University, who was recognized for her book “Cezanne’s Gravity.”

López-Durán traces how the “science” of race improvement spread from medicine to architecture and details how Latin American elites pursued utopian urban modernization projects under the influence of eugenics at the turn of the 20th century.

Far from being a topic of the past, race continues to inform the decisions we make today — in design and other matters — making “Eugenics in the Garden” as much a guide for navigating our future as it is a historical study.

We asked López-Durán about the way eugenics made its way across the Atlantic and Le Corbusier’s alignment with eugenics and his impact on global modernism. An edited transcript of the conversation follows:

Rice News: How did this book come about?

López-Durán: There are several answers to this question. When I was a Ph.D. student at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), I took two courses that were incredibly transformative: a course on histories and theories of the body taught by professor Arindam Dutta, and a course on nationalism taught by professor Robin Greeley. As a recent cancer survivor at the time, I was interested in better understanding my own body’s functioning, and as a Venezuelan living abroad during the first years of Hugo Chavez’s government, I was eager to learn about Latin American politics, so these two courses were irresistible. Simultaneously I took a class on ornamentation and modernism at Harvard with professor Alina Payne, and something clicked while writing a paper on Roberto Burle Marx’s gardens in Brazil for this class.

Roberto Burle Marx, mineral roof garden, Banco Safra headquarters, São Paulo, Brazil, 1983. (Courtesy The Jewish Museum/Photograph © Leonardo Finotti)

Without completely understanding the connection between medicine, ideology and the built environment at the time, I traveled to Paris for my first archival research to investigate possible connections between them. There, I visited the Musée Social — an uncommon archive for an architectural historian — because I had learned about a medical and moral practice called puericulture: a kind of human analogue to agriculture but for the scientific cultivation of the mother-child unit.

That’s when I found the seeds for “Eugenics in the Garden”: the complicity between physicians and architects working together in the Department of Social and Urban Hygiene. This complicity intrigued me, especially because I was motivated by a pressing need for architecture to be understood not as a hermetically sealed aesthetic structure but rather as the porous entity it actually is: permeated by critical issues of politics, science, security, economics and environment.

What are some real-life references to what you mean when you talk about the links between eugenics and urban planning?

“Eugenics in the Garden” examines a particular form of eugenics based on Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s theory of the “inheritance of acquired characteristics.”

My book examines a particular form of eugenics, which — based on Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s theory of the “inheritance of acquired characteristics” — conceptualized evolution as driven by adaptation to environmental changes. In contrast, mainstream eugenics viewed evolution as impervious to the environment and driven solely by genetics. Lamark’s form of eugenics traveled from France on the back of medical science and inserted itself within the urban fabric and architecture of early 20th-century Latin American cities.

The book focuses on the very clinical agenda that brought the human body to the center of modernist ideology, examining the complicity between science and aesthetics used to “normalize” a so-called feeble population in Latin America. In doing so, it reveals how eugenics, in its striving to create a new “human ideal,” found in medical science a moral guidepost through which architecture, urbanism and landscape design became its primary technologies.

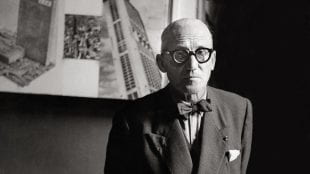

Within the framework of the book, did you choose Charles-Édouard Jeanneret — better known by his professional name, Le Corbusier — as an example of eugenics’ influence on the construction of the modern built environment, or did he emerge organically as a natural means of conveying this ideological evolution?

I was interested in learning more about Le Corbusier’s obsession with evolutionary theories, and I found a few hints of his flirtation with eugenics while doing research in Brazil and I read the transcripts of his talks in Rio de Janeiro in 1936. In his very first talk, Le Corbusier announced that he was going to write a book like “Man, The Unknown,”a best-seller that the Nobel Prize winner in medicine and eugenicist Alexis Carrel had published a year earlier.

Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier, in his atelier, 1955. (Photo by Imagno/Getty Images)

However, the connection between eugenics and Le Corbusier’s architectural doctrines was only clear to me when I had access to Le Corbusier’s own copy of Carrel’s book and to his archives in Paris. There I found revelatory documents, including the correspondence between Le Corbusier and Carrel — unpublished texts in which he literally linked eugenics and architecture, and the notes he took while attending Carrel’s talks. It was then that he began imagining a viable doctrine for the remaking of man in which the built environment would be put to work.

What does winning this prize mean to you?

All of my work is driven by the urgency to go beyond the celebration of forms and creators and beyond the geopolitical hierarchies that omit influential regions such as Latin America from our understanding of the global project of modernity. I am convinced that it is impossible to fully understand modern and contemporary art without exploring the transnational trajectories of ideas that conceived and shaped it.

Looking at the settings and politics that inform the making of art, architecture and culture in the so-called Third World, vis-à-vis Europe and North America, my work argues for an understanding of modernism as a product of multiple and often conflict-driven networks and transnational interconnections. So being the winner of this prize means the world to me, because it is not only a recognition of my scholarship but also a recognition to my activism — to my commitment to reconceive art and architectural history from global and interdisciplinary perspectives.

What do you hope others reading ‘Eugenics in the Garden’ will take away from it?

I hope people see the timely nature of this book and reflect on the key assertion that the book makes: Race constructs space, and space in turn constructs race. The global refugee crisis and other politically charged forms of segregation here and abroad makes it very clear that we are not living in a post-racial society, and that we need to understand the interactions of space and power by which race is instrumentalized. Racism was, and still is, the main tool in the geopolitics of space, and racism was, and still is, an ideology of so-called “progress.”