2019 INTRODUCTION | PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | LINKS

From astrophysicist to astronaut — and back

For Curt Michel, Rice’s proximity to NASA made the call to Houston in 1963 irresistible. Michel, a pilot and scientist who is now Rice’s Andrew Hays Buchanan Professor Emeritus of Astrophysics, dreamed of becoming an astronaut — and did, though he would never fly in space.

Michel’s academic career began in the 1950s, after three years of flying Interceptor jets for the Air Force in the skies above Europe. He studied physics as a graduate student at the California Institute of Technology, where Nobel Prize-winners Richard Feynman and William Fowler were among his mentors, and was recruited to Rice in ’63 as an assistant professor of space science by Alexander Dessler, who helped found the first-of-its-kind department earlier that year. (Michel himself later chaired the department.)

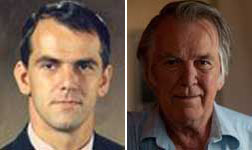

Then and now: Curt Michel, a pilot and scientist who is now Rice’s Andrew Hays Buchanan

Professor Emeritus of Astrophysics, dreamed of becoming an astronaut —

and did, though he would never fly in space.

Dessler and Rice President Kenneth Pitzer supported Michel’s wish to join the astronaut corps, and though Michel failed to make the grade when NASA selected its third group of astronauts in 1963, he became one of six scientist-astronauts admitted in the next group in 1965.

Because he was a pilot, he was able to begin astronaut training immediately while other scientist-astronauts were busy learning to fly. He experienced the full gamut of medical exams, endurance and survival training, and geological excursions.

He also worked on projects that would become part of the Apollo Applications Program — ways to use hardware derived from the Apollo flights — that included Skylab and the Apollo Telescope Mount, and took part in groups studying the lunar atmosphere. But there was trouble brewing in the ranks of the scientist-astronauts almost from the beginning.

”When we were selected at the urging of the National Academy, the idea was they wanted scientists to be sent to the moon,” Michel recalled. ”But when we got in, the astronaut office’s idea was to use the scientists after the lunar missions, in what they called ‘Apollo Applications.’ It was sort of a vague idea. Skylab could be argued to be an Apollo Application.”

Michel had another problem. Astronaut training and other NASA pursuits seriously limited his time for his astrophysics research. And by 1968, he saw his chances to fly were limited as the Vietnam War sucked money out of NASA and curtailed the number of Apollo missions. Helicopter training was required for those who would go to the moon, and none was forthcoming for Michel. ”For airborne craft, the helicopter was the closest in terms of characteristics to the lunar lander,” he said. ”So if you didn’t get helicopter training, you knew you weren’t going. That sort of gave it

Rice’s Curt Michel, third from left, dines on the traditional steak-and-egg breakfast with Neil Armstrong and others on the day Armstrong and David Scott blasted into orbit on Gemini 8. From lower left: Deke Slayton, the Manned Spacecraft Center’s assistant director for flight crew operations; Armstrong; Michel; astronaut Walter Cunningham; astronaut office chief Alan Shepard; Scott; and astronaut Roger Chaffee.

Michel took a year’s leave in 1968 to return to his research at Rice, where he continues to study radio pulsars and is working on a book about numerical methods. With further cutbacks in Apollo and few seats available for scientists on the upcoming Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz missions, he decided to leave for good the week before Apollo 11 touched down, a decision that became public a month later.

Michel was out of town July 20, 1969, vacationing with his family in Colorado and remembers watching the landing. “It was pretty amazing,” he said, and recalled feeling the sense of accomplishment that seemed universal that night.

He also took part in two fairly extraordinary events before departing NASA for good. One was a celebration of the landing at a dinner hosted by President Richard Nixon in Los Angeles, a black-tie affair held shortly after the Apollo 11 astronauts were released from their postflight quarantine.

The other was his participation in the debriefing of the Apollo 11 astronauts — records from which are available thanks to Michel’s habit of keeping items associated with his years at NASA. “I don’t think they let astronauts leave with anything now,” he said, but Michel’s treasures are a boon for Rice. He donated them to the Woodson Research Center for what is now the Michel Collection — dozens of boxes of NASA-related ephemera that contain his personal correspondence, memos, manuals, clippings, souvenirs, uniforms and other things he collected along the way.

Of particular interest are his detailed notes from the July 31, 1969, debriefing of Armstrong, Aldrin and Apollo 11 command module pilot Michael Collins, all of them still in quarantine after landing to allay fears of contamination from the moon. Such closed-door, astronauts-only meetings were held after every mission, he said, “so we could all hear what went on, who screwed what up — who let the parachute go too soon and all these little things. We got insights into operational stuff.”

His five pages of handwritten notes in a Rice-branded journal offer a unique insight into the astronauts’ views while the mission was still fresh in their minds.

For instance, there’s Collins’ comment about a docking mechanism that had to work perfectly — twice — to link the command and lunar modules: “I wouldn’t give a nickel for that thing working.”

About the harrowing lunar landing, Armstrong said he didn’t even notice the contact lights and couldn’t feel the craft touch down. Having piloted the lunar module over a crater and a field of “VW-sized” boulders, Armstrong dryly noted it “looks like we’ll have to plan on picking a landing site — can’t expect to end up at one.”

Michel’s notes on Armstrong continue: “Wanted to be careful of LM, yet Buzz broke off a ckt brkr and each inadvertently pushed one in. Egress simulation valid. [Man’s first act on the moon was to throw trash on it – Armstrong discarded a duffle bag with some junk in it].”

About walking on the moon, Armstrong said his boots would sink in a quarter-inch on the flats and 3 to 4 inches on the rims of small craters. “Need to anticipate (about) three steps in stopping. Could ‘lope’ about 6 mph.”

Armstrong noted the moon rocks they collected had an “odor like wet ashes” that Aldrin compared to cap-gun fumes.

“It was sort of informal,” Michel recalled of the debriefing. “They’d gather everybody up, and off they’d go.”

Michel contends that if he had not resigned when he did, Harrison “Jack” Schmitt — the only one in Michel’s astronaut class to walk on the moon — might never have done so. ”Jack wasn’t even on the agenda,” he said. ”Another guy was scheduled (for Apollo 17), but the National Academy of Sciences got all pushed out of shape when I left. I think that was largely influential in Jack getting his flight.

”When it looked like their primary idea of getting a scientist to the moon was going to flop, they finally started pushing their weight around.”

While scientific research might have taken a back seat at NASA, it was the only priority for space scientists at Rice in the ’60s who were scrambling to prepare experiments for Earth orbit and, soon, the moon.

Leave a Reply